Rain in the Desert

On the second night in, it rained. Imperceptible at first, but the tiny scattered droplets ran together across massive expanses of sandstone and the sound of water running down creases and dripping off ledges awakened me. I was in a perfect position to witnessing the phenomenon; tucked into a warm sleeping bag on a dry sandy shelf, a rock overhang protecting me from the elements. Protected, but not isolated as a tent can do, which made all the difference.

The rain picked up momentum, and consequently so did the rivulets draining off the ledges. Our campsite was surrounded on three sides by towering layers of sandstone and limestone. The south side opened to a narrow canyon, which eventually ran into a slightly less narrow canyon, and that one into another, and finally into the Grand. Thunder echoed off the thousand-foot walls around us, and rolled down the canyon. It was followed by more thunder in the distance, echoing off other walls and rolling down parallel canyons. So in the absolute darkness one had an auditory sense of the terrain; a maze of narrow canyons and stupendous rock faces.

Occasional brief flashes of lightning only served to produce a monochromatic scene that had a more disorienting than illuminating effect. It was not a fierce storm, and in the lulls between showers the sound of water trickling down crevasses mingled with the comforting shuffle of hooves on cobbles from the direction of our tethered horses. Nor was it cold, despite a gentle upcanyon draft hinting of wet  sandstone, sage, and juniper trees. It ended sometime before dawn, long enough for me to wake from a deep sleep when the sky was growing light. This time of year, mid-February, morning comes at a blissfully late hour and I luxuriated in the additional sleeping time.

sandstone, sage, and juniper trees. It ended sometime before dawn, long enough for me to wake from a deep sleep when the sky was growing light. This time of year, mid-February, morning comes at a blissfully late hour and I luxuriated in the additional sleeping time.

The wedge of sky I could see from camp was rapidly clearing; high clouds moving north across the canyon walls and the air quickly resuming its arid feel. In this world of rock varying in size from mountain to sand, mud is not a cause for concern. The worries associated with rain, or lack thereof, are flashfloods and dry springs. We saw the dramatic effects of flashfloods on several occasions during the week; watermarks on the canyon walls high above our heads and boulders the size of houses perched in unlikely positions. Fortunately we did not have firsthand experience with flashfloods, nor with the results of lack of rain, which usually means camping in less desirable locations near the desperately few reliable sources of water.

We packed up camp and climbed out of the canyon, crossing red sheets of slickrock speckled with scintilla ting blue puddles where rainwater reflected the morning sky. Most were not more than an inch deep, but our horses cleverly found the deepest ones and sucked down cold fresh water in long gulps. They were experts at this, knowing as they did that it could be a long ride to the next water hole.

ting blue puddles where rainwater reflected the morning sky. Most were not more than an inch deep, but our horses cleverly found the deepest ones and sucked down cold fresh water in long gulps. They were experts at this, knowing as they did that it could be a long ride to the next water hole.

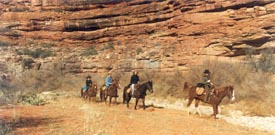

Ours was a relatively small group, 10 people, 12 horses and 3 mules. At times it felt very small and insignificant indeed, like when we were riding across one of the broad terraces, or in the depths of a narrow canyon with 800 foot walls. But gathered around the campfire in the dark evenings, or when it w as my turn to flip pancakes, our little group seemed much larger.

as my turn to flip pancakes, our little group seemed much larger.

Our guide, Mel Heaton, comes from a long line of ranchers born and raised in the strikingly beautiful but desolate country between the Colorado River and the Utah / Arizona border. He calls the stair step terraces of the Grand Canyon and its tributaries the “winter pastures,” referring to the local ranching practice of pushing livestock into the canyons for the winter months when there is water in the springs and natural tanks. A vertical walls over 1000 feet high on one side, and a vertical 1000 foot drop on the other are pretty effective fences. “The pastures are 40 miles long and 40 yards wide,” Mel says, “and the only places we have to fence off are where they open into a canyon.”

Mel sometimes winters his horses in these pastures, and I was the lucky beneficiary. My mount, a bay mare named Bell, spent several winters grazing the sparse feed and negotiating the rugged terrain of the winter pastures. Bell was beyond “sure footed,” possessing an almost uncanny ability to gracefully maneuver across everything from slickrock to fields of prickly pear cactus. The other riders had similar sentiments toward their mounts. When you see what those horses packed us through, you can imagine our sense of respect and gratitude.

In August of 1869, Major John Wesley Powell and eight men in three wooden boats, with dwindling rations and no idea where the Grand Canyon ended, were the first white explorers to document the amazing network of canyons and terraces which comprise this section of the Colorado Plateau drained by Kanab Creek. An entry in Powell’s journal reads, “From this point I can look off to the west, up side canyons of the Colorado, and see the edge of a great plateau, from which streams run down into the Colorado, and deep gulches in the escarpment which faces us, continued by canyons, ragged and flaring and set with cliffs and towering crags, down to the river.”

On our Grand Canyon ride we spent 6 days exploring the winter pastures, and in those days we discovered many things: no two canyons are the same, water is scarce even after a rainstorm, the ambient temperature can drop 20 degrees just by stepping into the shade, and the Colorado River is only one element of the Grand Canyon complex. The route we followed did not reach the Colorado River.

One afternoon we tied the horses to pinyon trees, and walked with our lunches to the edge of the terrace. Stretching away to the south was a maze of twisting and turning and intersecting canyons, which created islands and peninsulas grizzled with pinyon, juniper and sage. As ravens careened above and below us, we peeled oranges and gazed across the consecutively faded ridges to a distant pale blue line; the south rim of the Grand Canyon. According to the USGS topographical map, the river was churning and boiling its way through the main canyon some 2000 feet further down the terraced layers of geologic time from where we sat contentedly dangling our booted feet and eating sandwiches.

The final night, up on the rim, was cold and silent. Because we were back to the end of the road where we left the trucks 6 days earlier, it was a relatively comfortable camp with the luxury of tables and chairs. But the reassuring shuffle of tethered horses throughout the night was replaced with the lonely hoot of an owl. The horses had been turned out in their own winter pasture for a much- deserved rest. We were dirty from a week without bathing, admittedly a little stiff from sleeping on the ground, but emotionally relaxed and rejuvenated, and unanimously reluctant for reentry into the civilized world.

Ellen Vanuga

February 2003